The kind of partisan language you see on cable news is nothing new.

Spiro Agnew — Richard Nixon's vice president — was a champion at flinging barbs at political opponents and the media.

The kind of partisan language you see on cable news is nothing new.

Spiro Agnew — Richard Nixon's vice president — was a champion at flinging barbs at political opponents and the media.

Agnew ran for governor of Maryland in 1966 as a more palatable choice than the segregationist Democratic candidate.

This may have been why Blacks and liberals were surprised when his politics took a sharp turn to the right. Agnew shut down the state's predominantly Black college when anti-war protests broke out, and then he sharply criticized Black leaders for not doing enough to help end rioting after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Still, Agnew served his state in relative obscurity. The standard joke after Nixon named him his running mate in 1968 was: “Spiro who?”

After struggling with how to use the inexperienced Agnew effectively, the Nixon administration decided Agnew would make a great hahet man. Armed with hardhitting but alliterative prose written by White House speechwriters Pat Buchanan and William Safire, Agnew hammered Vietnam protesters, college students, minorities, the poor, the media — anyone, really, who differed with Nixon's policies.

“Ultraliberalism today translates into a whimpering isolationism in foreign policy, a mulish obstructionism in domestic policy, and a pusillanimous pussyfooting on the critical issue of law and order.”

Sept. 10, 1970, Springfield, Ill.

“Education is being redefined at the demand of the uneducated to suit the ideas of the uneducated. The student now goes to college to proclaim rather than to learn ... A spirit of national masochism prevails, encouraged by an effete core of impudent snobs who characterize themselves as intellectuals.”

Oct. 19, 1969, New Orleans

“I didn't say I wouldn't go into ghetto areas. I've been in many of them and to some extent I would say this; if you've seen one city slum, you've seen them all.”

— Oct. 18, 1968, Detroit

“There are people in our society who should be separated and discarded. I think it's one of the tendencies of the liberal community to feel that every person in a nation of over 200 million people can be made into a productive citizen. I'm realist enough to believe this can't be."

— June 30, 1970, British TV

“In the United States today, we have more than our share of the nattering nabobs of negativism. They have formed their own 4-H Club - the 'hopeless, hysterical hypochondriacs of history'.”

— Sept. 11, 1970, San Diego

By 1971, Agnew had grown into enough of a loose cannon that Nixon considered replacing him on the ticket with Democrat John Connolly. Connolly declined the job, so Nixon retained Agnew,

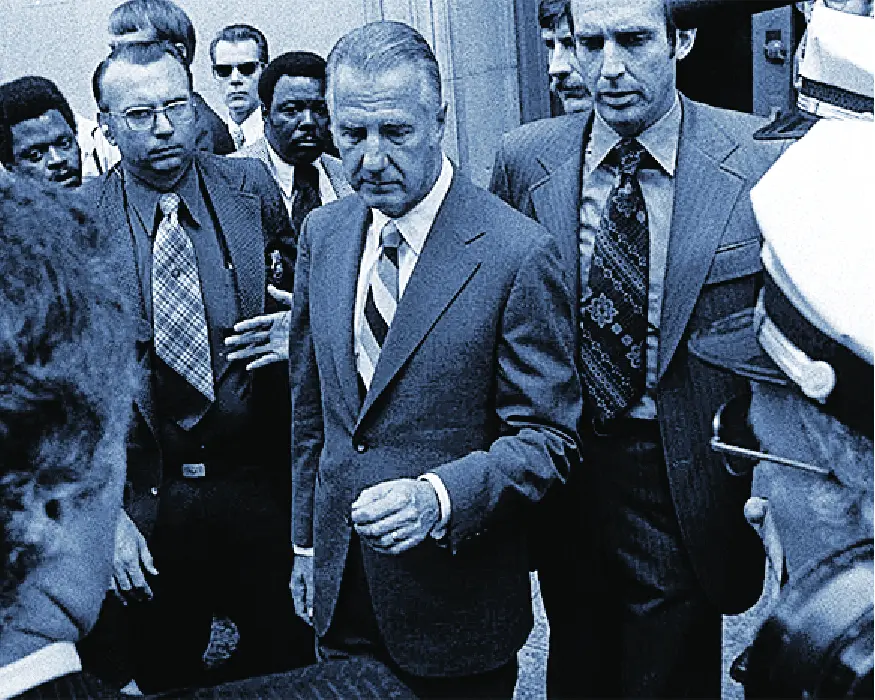

but keeping him in a reduced role. Shortly after Nixon and Agnew's second terms began, news broke that Agnew was under investigation for illegal campaign contributions as governor of Maryland.

Nixon, at first, made light of the accusations, noting that taking campaign contributions from contractors was “a common practice” in many states. “Thank God I was never elected governor of California,” he quipped.

But the allegations grew more serious. Agnew had continued to take money for past favors, even directly in his White House office.

- Sept. 29, 1973, Los Angeles

Eventually, White House chief of staff Alexander Haig helped negotiate a plea bargain: Agnew pleaded no contest to failing to pay taxes on cash contributions he had received.

On Oct. 10, 1973, Agnew received a suspended sentence, paid a $10,000 fine and agreed to resign as vice president.

Two days later, Nixon appointed House Republican leader Gerald R. Ford as vice president.

Ten months after that, Nixon — enmeshed in an enormous political scandal of his own — resigned and was succeeded by Ford, the first person to hold the office without being elected president or vice president.

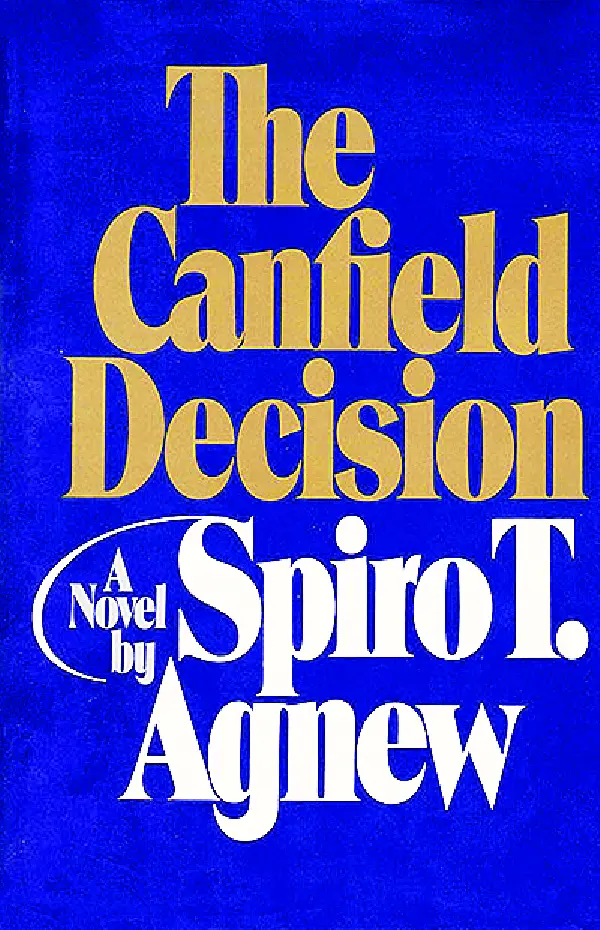

Agnew retired to Rancho Mirage, California — near Palm Springs — and went into the international consulting business. He also wrote two books: A 1976 novel about a loose cannon vice president “destroyed by his own ambition”...

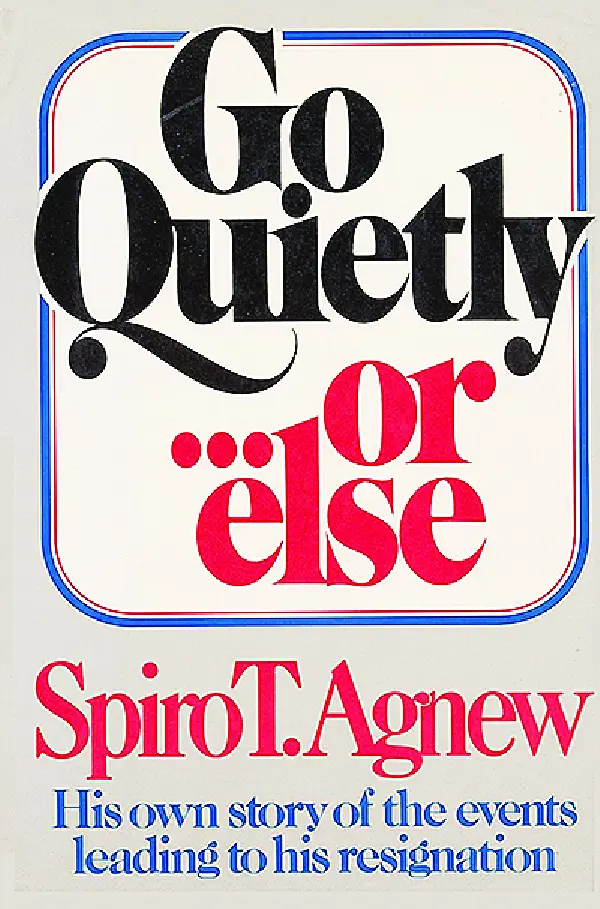

... And a 1980 memoir that suggested, perhaps, how he felt about his departure from government.

Agnew reportedly refused to take calls from former president Nixon but did attend Nixon's funeral in 1994.

Agnew died in 1996 of leukemia.

This edition of Further Review was adapted for the web by Zak Curley.